Common lisp - good parts

12 May 2017Since last summer I decided to invest some time into learning common lisp and wasn’t disappointed. Certainly, the language shows it’s age and there are some issues with documentation and libraries, but the benefits are so great that it’s hard to return to usual languages of choice.

A week ago we had a first Lisp and Scheme meetup in Amsterdam (please, join the next one!) and I’ve prepared a little talk to discuss what features I find especially affordable and powerful.

Since I’m not a perfect speaker by any means, here is a text version.

Intro

Tech culture is really spoiled by hacker news syndrome. If some corp © has a budget big enough to promote the language, we’ll see it all over the place, and of course, everything starting from cli parser and editor and ending with distributed systems will be implemented there. If they scream loud enough, it’s really easy to assume that these concepts or methods were invented there.

That leads us to a skewed perception of the world. We always think that we’re moving from some sort of dark ages towards something looking like bright future. It could be so but it’s not necessarily so.

Having no formal CS education certainly does not help. I started my career as a developer working with Pascal and Delphi, then moved on to the web development path where I mostly lived inside of a page request with languages like PHP or web page lifetime with Javascript. Although I did progress with understanding the whole stack from bottom to the top I was exposed to one specific way of doing things which is dynamic languages and it bothered me since web development is detached from system programming and associated languages. At some point I encountered clojure and it was no less than a turning point in my life. The experience was so different that to this point I can’t imagine spending my free time on something less powerful.

The core of the experience was of course in the interactive development which makes development so much faster, I’ll talk about it later.

When you have a language that powerful you want to write basically everything with it and having the jvm as a backend meant slower startup times which is not acceptable for cli programs. For sure there are hacks to fix that, but I wanted a cleaner solution and of course every flamewar around clojure had some sort of comparison to common lisp. So in the end I decided to go back to the roots and to try it out and learn the language.

So, common lisp. Some of it’s concepts may look surprising but were not uncommon in the early nineties. I’m not a Common Lisp expert, so the rest of the post is not an authoritative source, but more my perception of the language at the time of writing. If you see anything clearly wrong, please tell me.

I’ve taken three different aspects which are notable for me one section for each. Here we go.

Stability

A small section for the big feature. Stability of Common Lisp as a language and platform is remarkable. It’s specification was in the works for ten years and hasn’t been changed since original publication. There are constant debates around this, every year or two one more attempt to modernize language pops up. For sure they target some problematic areas but problems are not so severe for these projects to get traction.

From the other side specification is really complete, so you can see a defined behavior for any corner case (even if it’s specified as an implementation defined - these places usually talk about the internals of the language). There are around 10 different compilers that are actively developed and provide different sets of features and most of them have been in development for years so you can imagine the level of robustness there.

I would say that sbcl is more or less a default choice at the moment, and there are differences between implementations as there are compiler specific packages and apis, so it’s not all roses.

Code that was written fifteen or twenty years ago can run on any modern compiler. How cool is that?

Interactive development

Interactive development is one of the major features of the common lisp and a cornerstone of the language design. Everything was made in a way to allow this method of development.

The easiest way to show this is to outline how development happens in common lisp and in classic languages.

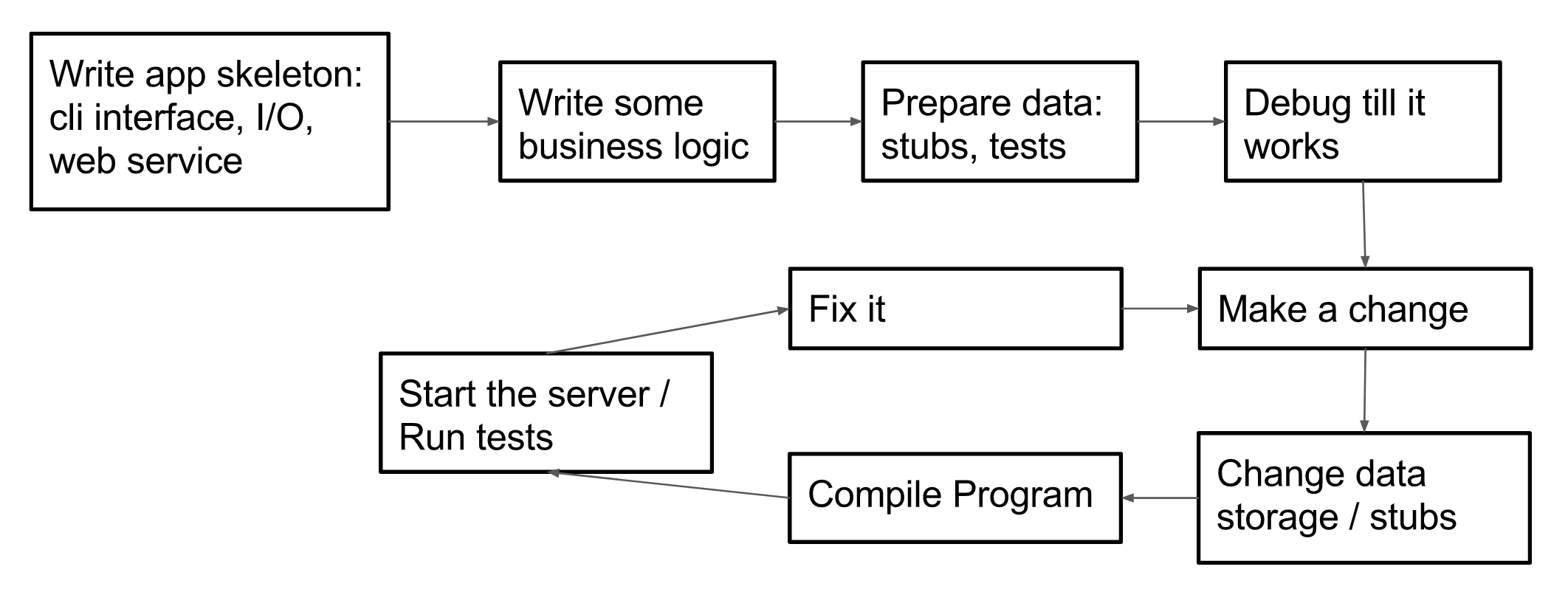

Most programming environments do not provide too many tools to understand and change the state of the running process, I’m not even talking about actual development there. In some the only way is printing data into STDERR, in others you can use a debugger to set a breakpoint and look around. Frontend developers are luckiest in this case - web page is really easy to introspect by definition and there are ways to do bits of interactive development there (just look at all the excitement about css hotloading) and it’s also a place where it’s easy to feel the difference. Once you have a dynamic page and build pipeline you immediately lose in productivity and it requires more and more efforts to compensate. In other environments you face a necessity of building program interface from day one - write cli interface, make assumptions about the structure of data and prepare some stubs, understand how this data gets into the program and back from it. Depending on requirements it can take few hours or few days to get this fully working, and that’s the time you could spend on solving the main problem.

Anyway, after finishing with that you get into a usual cycle of development. You make a change, change all the data storage etc. to accommodate for new data structures, compile and restart server / run tests, where you’ll load all stubs and hopefully get the desired result. If not you penetrate your program with all sorts of print statements just to understand what happens.

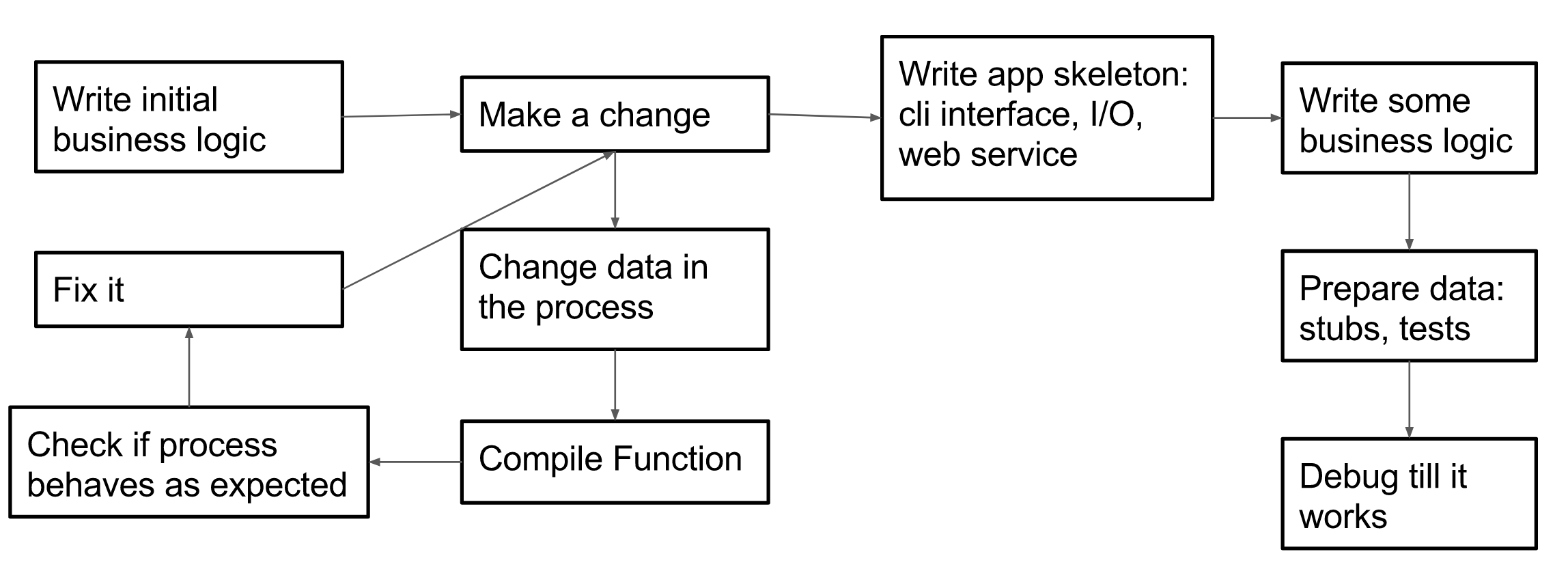

Interactive development in common lisp is different in sense that you start

developing by starting repl-process and you can already start solving problem

and write necessary business logic, all the stubs can be generated

programmatically and put into the variables as you go, No cli interface is

necessary. While being attached to the process it’s possible to access any

package, inspect any variable, change any data structure and define or change

any new function. That means that change cycle is reduced to change code ->

recompile function and all proper interface is moved to a later stage.

All this does not deny testing, it’s just that you do not rely only on it and can have much quicker troubleshooting cycle. Moreover, in many cases you can live without a proper external interface for a long time or not need it at all if your task is only to calculate something or prove the idea and you won’t lose any flexibility because you’re calling your code directly by passing language data structures. Btw, this is another advantage which is everywhere in common lisp - in many cases you don’t need to parse strings or invent serialization formats you can easily use language data structures.

That’s actually how any lisp program works - lisp process starts, loads and compiles some lisp code and runs some function on it. Why it works like this is because CL is an image based language - during the interactive development session developer shapes the program to a particular state where he can dump the image into a binary file and this is a default way of compiling programs in common lisp.

(ql:quickload 'trivial-dump-core 'your-awesome-project)

(trivial-dump-core:save-executable

"awesome_project"

#'your-awesome-project:main)

What happens when you dump image? All the environment is dumped there -> you have a compiler etc when you run it again Startup time of the image is really fast - ~10-30ms Dumping state means saving all the memory state like variables and that means that theoretically you only need to dump image of problematic environment to get all the information Dumped image has no dependencies, so it can be safely deployed as one file.

Extensibility

An important point is that the word “Common” in Common lisp means that the language was created as a response to the existence of many slightly or very different lisp dialects that had to be united. On one hand, it resulted in some duplication (like structs and classes), on the other hand, extensibility is a cornerstone there are ways to extend lots of different aspects of the language or program.

Assignment

What can be simpler than plain assignment? Really, nothing to see there. We can assign to variable, or maybe have a setter on the object.

var variable = "value";

myObj.variable = "value";

In common lisp the operation is generalized to setting the result of form to a place.

(setf <place> <form>)

While <form> is easy, <place> is much more interesting, because variable is

only one of it’s possible meanings.

(setf var "value")

(setf (aref var 2) "value")

(setf (some-field obj) "value")

(setf (my-storage :key) "value")

You can define a function call as a setf, e.g. (aref arr 0), or

basically any other form via the macro, so that you can have mirrored get/set

interface in almost any imaginable case and it will work consistently via setf.

For example all the getters for the object fields are defined with setf

extensions.

Generic functions

Generic functions are one of the fundamental parts of the Common Lisp and they are fantastic in a way that although they are dispatched against types they are totally decoupled from them - all of them, not just the first one. Common Lisp automatically orders implementations against declared types and chooses the most specific implementation for every call. As a consequence new functionality can be easily implemented against any existing class hierarchy, even defined in the other library.

For example we work with some kind of DOM tree and want to print it in our specific way. We can define a generic function, give default implementation for it and add any number of specific implementations for certain kinds of elements.

(defgeneric print-xml (stream element &optional indent))

(defmethod print-xml (stream (element <element>) &optional (indent 0)) …)

(defmethod print-xml (stream (element <dict-article>) &optional (indent 0)) …)

And that means that you don’t have to make a wrapper on such classes or do inheritance just to add a method, you can just implement business logic against it.

Another advantage is that with generics we get another way to group functionality - around functionality and not around objects.

As if that wasn’t enough generic functions come with a complete support of

aspect-oriented programming with :before, :after and :around modifiers. That

adds yet another direction of extension and may libraries and common lisp as a

language define generic functions as external api so that clients can add hooks

in to particular points in the program without passing lambdas around.

Suppose there is a database of posts that exposes delete-post generic

function. We can remove all the I/O operations from this library and plug it

externally.

(defmethod delete-post :after ((db <db>) (post <post>))

(save-posts))

By defining a generic function library exposes not only one but multiple extensions points which can be used without touching the library code.

When generic function is defined developer also defines a way how dispatching works. By default the most specific method runs, but you can use several others like sum, aggregate or even define your own.

CLOS

CLOS is an object system for common lisp that supports many features that make it very advanced.

Class in common lisp is a bag of slots. During definition developer defines properties of every slot, so that it’s possible to define how slots are read or initialized.

Since functions are detached from objects, it makes it easier to have multiple inheritance and CL supports that. Every getter on the slot is defined as a generic function with implementation specific to this class but nothing prevents to redefine getter/setter.

One of use cases for multiple inheritance is when you need to use two independent concepts. Let’s look at the following example that I stole from the “Art of Metaobject Protocol” book.

(defclass <rectangle> ()

((height :initform 0.0 :initarg :height :reader height)

(width :initform 0.0 :initarg :width :accessor width)))

(defclass <color-mixin> ()

((cyan :initform 0.0 :initarg :cyan)

(magenta :initform 0.0 :initarg :magenta)

(yellow :initform 0.0 :initarg :yellow)))

(defclass <color-rectangle> (<color-mixin> <rectangle>) ())

(defgeneric paint (x))

We have a generic function paint and a <color-rectangle> class that

inherits from <color-mixin> and <rectangle>. We can implement function

itself against <rectangle> class and it will, well, draw a rectangle. After

that we can implement :before method against <color-mixin> that will setup

brush properties and maybe :after method to reset them. By doing that we

decouple two separate concerns and it’s trivial to implement any other shapes

with color support.

CL went one step further and made all the definitions in common lisp as instances of standard objects, which means that e.g. class definition is an instance of the class “class definition” and can be extended. With that CL provides multiple generic functions that are dispatched against standard objects and it’s possible to create a subclass of standard objects and change the behavior of the particular objects. As a result CLOS covers not only one specific way to implement an object system (although default way is provided) but a wide spectrum of possible implementations.

Macros

To get the idea about possible use cases for macros let’s consider the following example in some javascript like language.

class Widget {

constructor(height, width) {

this.height = height;

this.width = width;

},

run() { /* useful stuff */ }

}

API.registerWidget("Widget", Widget)

Is there any code duplication there? In javascript you’ll say that there isn’t since all the lines are the necessary boilerplate to make things work. Let’s imagine a perfect world and choose the best syntax for this case. Wouldn’t it be nice to write something like this?

defWidget Widget(height, width) {

/* useful stuff */

}

Here is a possible implementation in case of Common Lisp.

(defmacro define-widget (name params &rest body)

`(progn

(defclass ,name () ,(expand-params params))

(defmethod run ((widget ,name)) ,@body)

(register-widget ,(symbol-name name) ,name)))

Easy.

Macros provide a way to fight with code duplication and inefficient computation on the whole new level. Since macros are expanded and evaluated on the compile level, we get two advantages: we can offload intense computations on the compilation step if possible of course and code duplication can be chased now not only on the logic level but really on the syntax level.

In addition to that CL provides a way to define reader macros so that you can tune your program code to your liking. The big difference between lisp macro system and say c macros is that lisp macros work with a source code as a code data structure that is easy to manipulate with all the power language provides and not as a simple substitute.

Conclusion

I hope I’ve made a showcase for CL and you’re interested to try it out if you haven’t done it before. It’s not all roses and I have to give a word of warning there - the situation with documentation is mediocre, even some popular libraries can have problems there, there is plenty of outdated code or broken home pages. The language itself has duplication in some parts like mapping functions or binding variables and lacks some essentials like complete library to work with strings, community is much smaller than in any hype language.

On the other side there are libraries to compensate shortcomings of standard library and many interesting projects in different areas, some of them are really brilliant (see Mezzano as an example).

If you want to read about language in general, the best book ever written on CL on my opinion is Peter Seibel’s “Practical Common Lisp”. It’s an invaluable gift to humanity and what’s more it is freely available online. Another piece of art on the topic is “The Art of Metaobject Protocol” which is very interesting to check out to understand decisions behind the CLOS design. First part of the book is dedicated to the implementation of simplified CLOS and is amazing. And as I’ve told in “Stability” chapter, the fact that the book is from 1991 doesn’t mean it’s outdated :) There are other books like “On Lisp” from Paul Graham, but they can be read on much later stage to get to the new levels of enlightenment.

Quickdocs website is a place to go if you want to find some library.

If you want to get help #lisp and #lispgames on freenode.net have the highest concentration of lisp devs alive, lisp reddit is worth checking.

Have fun!